Blood in the urine

To better understand your symptoms, visit us for a comprehensive diagnosis and personalised treatment plan

Blood In The Urine

My doctor told me I have blood in the urine. Should I be worried?

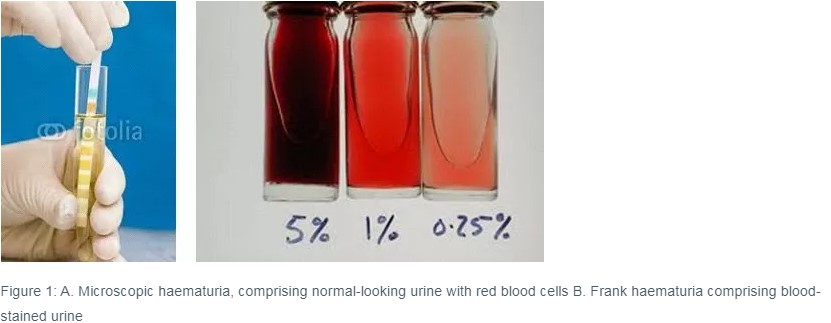

Blood in the urine, usually refers to the presence of red blood cells in the urine, known as haematuria. There are two main types of haematuria: (1) microscopic haematuria, where normal-looking urine contains small traces of red blood cells detectable only under microscopy, and (2) frank haematuria, where the urine looks reddish and clearly blood-stained (Fig. 1).

Microscopic haematuria without symptoms is a very common finding on routine health screening, and in almost 90% of cases are not associated with significant diseases after evaluation of the urinary tract. However, more than 50% of patients with frank haematuria will have significant findings on evaluation of the urinary tract.

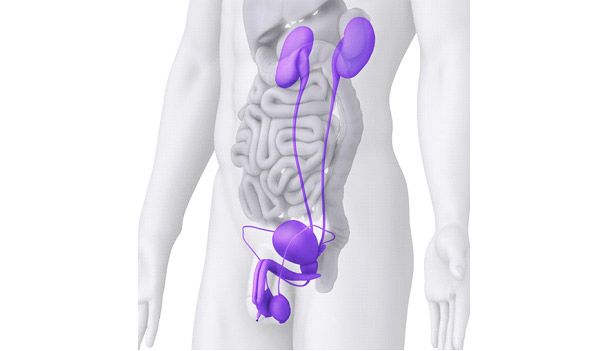

Urine is produced by the two kidneys situated in the abdominal cavity. It is excreted down long narrow tubes called the ureters into the bladder. When the bladder is full, urine is passed out through the prostate and urethra in men (in women, the prostate is absent) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The urinary tract in males, comprising the kidneys, ureters, bladder, prostate and urethra. The prostate gland is absent in women.

In Singapore, the three commonest causes of blood in the urine are infections, stones, and cancers or growths of the kidneys, ureters, bladder or prostate. Less common causes of haematuria include (1) trauma/ injury to the urinary tract; (2) kidney diseases such as autoimmune nephropathy and glomerulonephritis; (3) benign familial haematuria; and (4) sickle cell trait. Your general practitioner is likely to refer you to a urologist for further evaluation of blood in the urine.

To identify the correct cause of blood in the urine, your urologist will start by asking some questions pertaining to your urinary tract. These may include the following:

- Do you experience pain or difficulty passing urine?

- Do you experience difficulty emptying your bladder entirely?

- Do you have to go to the toilet frequently?

- When you have to go to the toilet, must you run to the toilet before urine leaks out?

- Have you experienced urinary leakage?

- Have you had recent loin pain, fevers or chills?

- Do you wake up at night to pass urine? If so, how many times?

He / she will then perform a physical examination, with the aid of bedside ultrasonography if available. Thereafter, your urologist will likely order some routine blood and urine tests to assess the function of your kidneys, and to see if any bacteria are present in the urine. He will also order a multi-phasic computer tomography urography scan with intravenous contrast, which nowadays has superseded conventional intravenous urography as the gold standard for imaging the urinary tract. In patients above the age of 35 years old, your urologist may also recommend cystoscopy to evaluate the bladder, prostate and urethra.

A CT urography scan with intravenous contrast takes about 10-15 minutes to complete, and is performed in the Radiology Department. After a preliminary scan of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast (to look for urinary stones), the radiology technician will inject intravenous low-dose iodinated contrast through a small intravenous cannula in the dorsum of the hand. The scan is then repeated 2 and 10 minutes later to assess for any abnormalities in excretion of contrast down the urinary tract, and to look for enhancing lesions such as tumours or cancers. Multi-phasic CT urography is the imaging procedure of choice because it has the highest sensitivity and specificity for imaging the upper tracts1 (Fig 3).

Figure 3: Reconstruction of the urinary tract on multi-phasic computer tomography to visualize the kidneys, ureters and bladder.

In patients with existing kidney impairment, the intravenous contrast poses a small risk of causing further damage to the kidneys. Nowadays, this risk is mitigated by using low-dose iodine contrast together with agents like N-acetylcysteine2. In patients with contrast allergy, magnetic resonance urography is an acceptable alternative imaging approach.

Cystoscopy is a simple procedure where the urologist passes a flexible endoscope through the urethra into the bladder, usually with the aid of a local anesthestic cream. Once the scope is passed into the bladder, the bladder is filled with clear irrigation fluid to allow careful inspection of the bladder lining for signs of cystitis, bladder stones and cancerous changes (Fig.4). For areas suspicious of cancerous change, urine may be taken for cytology and biopsies taken of these areas for detailed microscopic assessment for cancer cells. Cystoscopy is usually painless in women given the short length of the urethra in women, but may be somewhat uncomfortable for men. In this situation, male patients male choose to have the cystoscopy performed under intravenous sedation.

The American Urological Association’s 2012 Guidelines recommend that patients with a negative work-up for persistent asymptomatic microhematuria, should repeat their urine analysis and blood pressure checks once a year. If the microscopic hematuria persists after three to five years, repeat evaluation should be considered1. If the patient develops hypertension or protein in the urine during this follow-up period, further evaluation of the kidneys should be undertaken by a nephrologist.

References:

1. Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA et al. Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microscopic haematuria: AUA Guidelines (2012). American Urological Association. http://www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/asymptomatic-microhematuria.cfm

2. Wollin T, Laroche B, Psooy K. Canadian guidelines for the management of asymptomatic microscopic haematuria in adults. Canadian Urological Association Journal 2009; 3(1): 77-80.

3. Tepel M, van der Giet M, Schwarzfeld C, Laufer U, Liermann D, et al. (2000) Prevention of radiographic-contrast-agent-induced reductions in renal function by acetylcysteine. New England Journal of Medicine 2000; 343: 180–184.