Hernias & Groin Lumps

To better understand your symptoms, visit us for a comprehensive diagnosis and personalised treatment plan

Hernias & Groin Lumps

Doc, I recently noticed a lump in my groin. Is it a hernia?

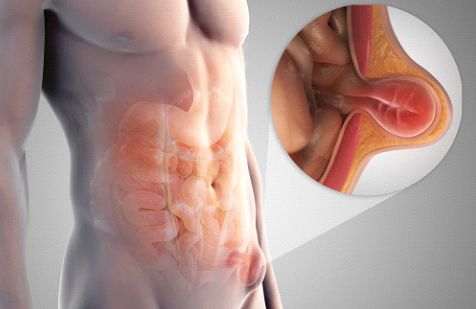

A groin hernia refers to the protrusion of abdominal contents such as fat, small or large intestine through an area of weakness in the lower abdominal wall. These contents are wrapped in the inner lining of the abdominal cavity to form a balloon-like sac (Fig. 1).

Illustration

Figure 1: Illustration of a hernia, where abdominal contents protrude through an area of weakness in the abdominal muscle wall.

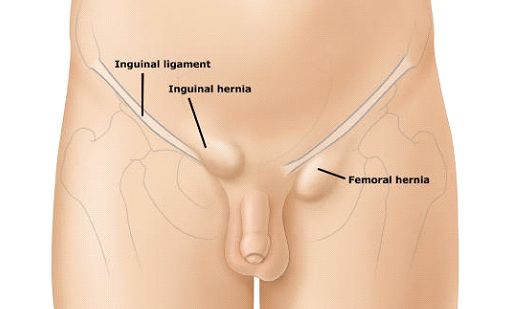

The majority of lumps in the groin are inguinal hernias (Fig 2). Less common causes of groin lumps are (1) femoral hernias; (2) swollen lymph nodes; (3) cysts or fatty lumps called lipomas of the spermatic cord; and rarely (4) swollen veins known as saphena varix. To identify which is the most likely cause for your groin lump, your doctor will usually ask you to lie down and cough a few times to see if and where the lump bulges out, and repeat the same manoeuvre with you standing upright. For greater accuracy, he may order an ultrasound of the groin to better visualize the anatomical location and contents of the lump.

Figure 2: Causes of groin lumps may be identified by their location relative to the inguinal ligament.

Groin hernias may develop at any age. In infants and young children, these congenital hernias arise at birth, whilst those that arise in adulthood are commonly associated with excessive straining of the abdominal muscle wall due to obesity, chronic cough, repeated heavy lifting, constipation, or straining to pass urine due to prostate enlargement. Men are eight times more likely to develop a groin hernia than women, and twenty times more likely to require surgical repair of these hernias.

Inguinal hernias are a common occurrence, and for the most part are not harmful. They usually cause intermittent pain and/or a dull ache in the groin, and in some cases a visible bulge when patients cough or stand up. In more severe cases, the hernia contents cannot be reduced back into the abdominal cavity (incarcerated hernia), and if the blood supply to these bowel loops or fat is blocked (strangulated hernia), patients may develop constant severe, unremitting pain and tenderness over the bulging area, associated with fever and vomiting. In this scenario, patients are best advised to seek immediate surgical treatment before the situation worsens.

Inguinal or femoral hernias arise due to areas of weakness or defect in the abdominal wall. As such, the only definitive treatment for these hernias is surgery. Patients who notice increasing pain, discomfort, tenderness associated with their groin lumps with should seek early surgical repair before the abdominal contents become incarcerated or strangulated, which may require much more complex surgery to fix the problem. Watchful waiting may be recommended for men with asymptomatic reducible inguinal hernias. However, watchful waiting cannot be recommended for women with femoral hernias, as the risk of hernia strangulation is significantly higher in this group of patients.

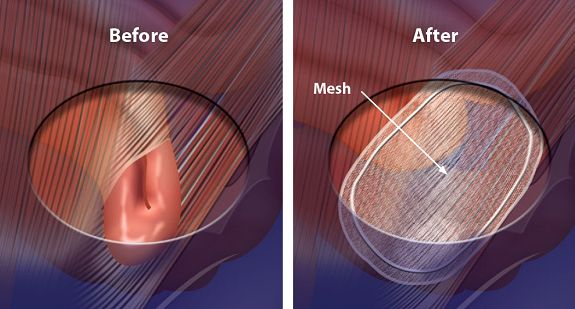

Surgeons performing surgical repair of inguinal hernias follow time-tested principles (Figs.3,4):

- Clear identification of the hernia sac or areas of defect in the muscle wall

- Reduction of the hernia sac and its contents back into the abdominal cavity

- Definitive repair of the abdominal wall using sutures and/or meshes

Figure 3: Illustration of the principles of surgical hernia repair, where the hernia sac and its contents are returned to the abdomen, and the areas of weakness of the abdominal wall are repaired with sutures and an absorbable mesh

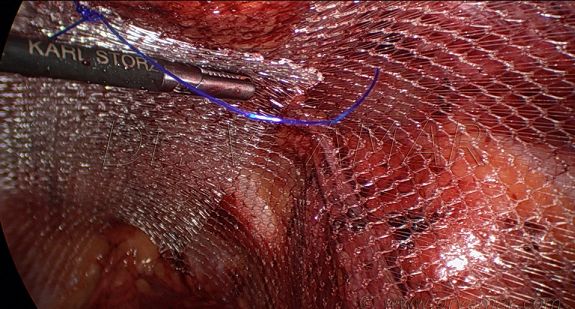

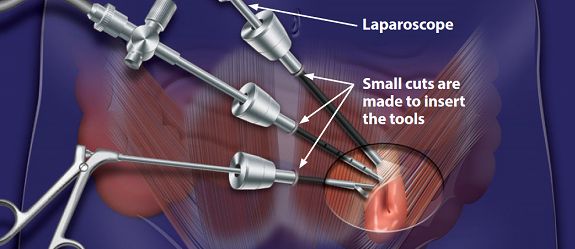

Figure 4: Surgeons using an absorbable mesh to cover the areas of weakness in the abdominal wall during laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery.

Repair of inguinal hernias may be performed using a conventional groin incision, or laparoscopically through small keyhole incisions <1cm. Most patients return home on the day of surgery, and the sensation of soreness over the wound usually resolves after 1-2 weeks after surgery. In 90-95% of patients undergoing hernia surgery, the repair is successful and the hernia does not recur.

Minimally invasive (laparoscopic) surgery has several advantages over conventional surgery – the incisions are small and look nicer; patients have less pain and quicker recovery after surgery; and are able to return to work and regular activities much sooner (Fig. 5) . However, laparoscopic surgery costs slightly more than conventional open surgical repair, and in some cases may not be feasible or be the most appropriate approach. Some of these scenarios include (1) painful incarcerated or strangulated hernias; (2) large hernias extending into the scrotum; (3) patients being morbidly obese; and (4) patients not being able to tolerate general anaesthesia. In such scenarios, open surgical repair still gives the best clinical outcomes.

Figure 5: Illustration of laparoscopic (keyhole) repair of an inguinal hernia performed through small incisions.

The most common concerns immediately following surgical repair of inguinal hernias are (1) bleeding and clot formation (haematoma); (2) inability to urinate due to spasm of the bladder opening (acute urinary retention); and (3) infection of the surgical wound, characterized by redness and tenderness or pus coming out from the wound site. Late complications after hernia surgery include (1) persistent pain that does not go away (usually due to entrapped nerve), (2) shrinkage of the testicle on the side of hernia repair (due to injury of the testicular vessels), and (3) recurrence of the hernia after some time. The last scenario tends to occur if the predisposing cause for the hernia remains untreated, such as chronic cough, constipation or straining to pass urine.

Most patients are able to return to work 1-2 weeks after hernia repair surgery. Most patients will be able to resume daily activities and sports 4-6 weeks after surgery, depending on their surgeon’s recommendation. Until such time, they should refrain from lifting heavy objects (such as carry-on luggage or young children), or strenuous exertion in the gymnasium.

1. Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability. World Health Organization 2007.

2. American Academy of Paediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Paediatrics 2012; 130(3): 585-586.

3. Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J. Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009; 15(2): CD003362.

4. Tian Y, Liu W, WangJZ et al. Effects of circumcision on male sexual functions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Journal of Andrology 2013; 15(5): 662-666.